This is an overview of the early history of writing and illustrating children’s books.

Please print this page, if you wish. I hope it will lead to feedback and opinions from readers.

The illustrations are taken from books in my collection. I will be very pleased to add others of early books, with acknowledgement, if people would like to contribute.

Do countries with an English heritage still produce the greatest proportion of authors of entertaining books for children, as compared to authors of all kinds of books? And fantasy? Why?

Every time I listen to editors of children’s literature, or read about the height of slush piles (piles of manuscripts not yet read by publishers’ editors), I get the feeling that Australia, where I live, is a nation of writers who secretly wish they were able to return to their childhood. We love writing for children, creating and sharing in their laughter, rejoicing in their imagination…and it is only with the greatest reluctance that we admit to being adult, believing, like Dr Seuss, that “…adults are obsolete children.”

It’s strange that wonderful prose, poetry and plays have been written for thousands of years world-wide, yet entertaining children’s books have been creations only of the last three centuries – and then mainly since Victorian times, and in countries with an English heritage.

Through the previous generations, and in other cultures and countries, children have been regarded as adults in the making – to become hunters, warriors or workers, or bearers and nurturers of the next generation. Though other European countries have produced a few great children’s writers, certainly in the early days of writing for children’s enjoyment, it is the ‘English Imagination’ that has dominated this literary sphere, and I wonder, does this continue to be true?

This special ‘English Imagination’, related to the love of nature, can be traced back to the Druids and Celtic times. It’s shown in the inventive illumination of early manuscripts, with fictional beasts contorted into knot patterns woven through letters and used for decoration. Until the end of the 17th century, however, books for children were written only for instruction, religious teaching and producing moral citizens…rather than for reading pleasure.

Some of the earliest books for children are the Venerable Bede’s 7th century text on natural science, the teaching books of the 11th century written by Alcuin of York, and, also from the 11th or early 12th century, the first ‘encyclopaedia’ for children, by Anselm.

Another early writer for children was Geoffrey Chaucer. He wrote a Treatise on the Astrolabe in 1391 for his son Lowis, but I don’t know how many times Lowis would have pleaded “Read it again, Dad. Please!”

There were many more authors in the 15th and 16th centuries who wrote ‘manuals of good conduct’ for children, called ‘Books of Courtesy’—but I don’t think many boys or girls curled up with them to read them for a laugh.

It was during the Renaissance that ‘popular literature’ was first produced – for adults. I wonder how many people could actually read at that time, and what kind of people actually bought the books?

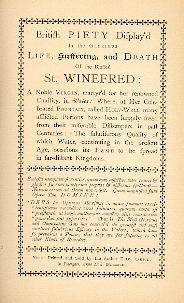

‘Chap books’ sold by peldars, from the late 1500s through to the Victorian era, provided religious stories and commentaries, romances and ballads. Nursery rhymes, legends of Robin Hood and King Arthur, and Fables started to be told to children – but I haven’t found when were they were first available in illustrated book form.

A chap book

Ballads of Robin Hood started appearing in the 14th century. The Arthurian Legend was described in the 12th and 13th centuries, retold verbally through generations to follow, written by Mallory in the late 15th Century and then by Tennyson in Victorian times.

In 1693, John Locke was the first to suggest the idea that children should read for pleasure, and recommended stories by Aesop. (It is not certain who Aesop really was. I have read that he may have been an advisor to King Croesus of Lydia in the 6th century BC, but the first written collection of fables, designed for adults, appeared in the 4th century BC…but I don’t know anything about later editions.)

People thought this idea of providing children with books for enjoyment was crazy, and it failed to catch on, though when hymn composer Isaac Watts wrote Divine and Moral Songs for Children at least some lines had a fun ring to them, like “How doth the little busy bee…”. The dawn of writing for children was about to break.

Writing for the entertainment of children first appears to have occurred in France, where Charles Perrault wrote Mother Goose for his own children. In it were simple versions of ‘Little Red Riding Hood,’ ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ and ‘Puss in Boots’. These stories, however, were not his original creations, and had been handed down orally over previous generations.

The first English translation of Mother Goose appeared in the early 18th century. Can anyone tell me if either of these was illustrated, or when the first illustrated version was published …in either France or England?

I don’t know how popular these editions were, for, even in England at this time, children were still considered miniature adults to be preached to and taught.

(Also written in the early 18th century were Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Gulliver’s Travels (1726). Neither were intended for children, but when abridged versions appeared, they were eagerly devoured by young people, and each provided a stimulus for later writing for children. I’m not as well-read as I would like to be. Can we go back farther than Gulliver’s Travels for the first fantasy realm??)

A small instructional 12 page book called A Little Book For Children seems to have been the first book to have actually been written from a child’s point of view. Not much is known about its origin. It’s undated and written by an author with the initials T.W., but it’s believed that it was produced in the first decade of the 18th century.

One of the earliest, if not the earliest English publisher of fun books for children, was Thomas Boreman. Records show he was in business publishing educational books in 1730, but on his list for 1742 was a title called Cajanus, the Swedish Giant, which sounds as though it might have been entertaining. However, John Newbery is thought of as the ‘Patron Saint of Writers of Books For Children’— hence the ‘Newbery Medal’—for it was he who first realised there was a market for such products. Speaking of him, Oliver Goldsmith wrote in 1766, ” (Newbery) …who has written so many books for children, calling himself their friend, but who was the friend of all mankind.”

As an author, editor, publisher and bookseller, John Newbery made this niche of ‘entertaining children’s books’ his own. His book of 1744, Little Pretty Pocket-Book, had pictures of children’s games, fables, rhymes and more, and I believe is the first known book to have been created purely for children’s enjoyment. I have not yet discovered, however, details of any other books Newbery was involved with.

My only copy of a pre-1800 book for children’s enjoyment is this hieroglyphic bible “…with emblematic figures (wood-cuts) for the amusement of youth”. It is dated 1791, and is a ninth edition.

After Locke, Rousseau, in the 1760’s, was the next influential person to consider that children should be considered and treated differently to adults, but again this notion was mainly ignored and books continued to focus on creating moral and exemplary conduct.

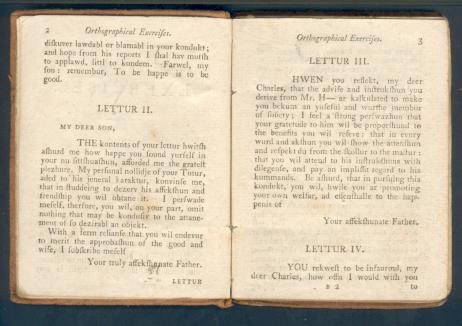

A book of moral letters (c1800) designed to teach pronunciation.

The first books of humourous or entertaining poems written especially for young children were Original Poems For Infant Minds and Rhymes for the Nursery, written in 1804 and 1806. The former was written by a mixture of authors, including Ann and Jane Taylor, and the latter, which included ‘Twinkle, twinkle, little star…’, by the Taylor sisters alone. (I wonder, could I be related?) Great nonsense verse, however, was non-existent before Edward Lear’s Book Of Nonsense masterpiece was written in 1846.

Pages from an original copy of Peter Piper’s Practical Principles of Plain and Perfect Pronunciation

The early 1800’s saw the traditional fairy stories and more rhymes popularised in Henry Cole’s Home Treasury series.

In other countries, the Grimm brothers Children’s and Household Tales (Grimms’ Fairy Tales) were written in 1823 -26 and those of Andersen in 1846, but, for the most part, stories were the retelling of old sagas and folklore rather than inventions of the author’s own imagination—the forte predominantly of the English.

I am not a historian, and would be interested to learn why the Victorians in England suddenly seemed to ‘lighten up’, to kindle and bask in the new-found flames of light-hearted entertainment at home. Could it have been their wealth created through the Industrial Revolution (though the poor were a highly significant proportion of the population)? Adults played games with forfeits, enjoyed music, satirical writing, cartoons and much more, and also delighted in the laughter of children.

A book of forfeits, dated 1833, for adults and children.

This was the first time that children were really appreciated for their special qualities and imagination. This joy in the recognition of the nature of a child to be ‘different’ from that of an adult was, and is, the essential requirement needed to provide adults with the freedom to use their own creative imagination in writing, what we now recognise as, ‘children’s books for pleasure’. What finer way to celebrate this recognition of difference than the writing of Alice in Wonderland, published in 1865 – possibly the cornerstone of all our output of personified animals and animated objects?

Though the great genius of inventive writing, Jules Verne, was born in France, and every country has had its stand-out authors, generally, in Europe, the ‘latins’ in the south have far less of a tradition of imaginative writers than Britain, Germany and Scandinavia. I have read that this is related to the southern acceptance of church and other authoritarian control through fear, and the possibility, if not belief, that children mature quicker there.

For generations, education in France has started with focusing on logic and reasoning, with little reference to poetry and literature, and imagination has not been encouraged. Not surprisingly, most of their children’s books have had different themes to those from other countries.

In America too, some writers point to a north – south divide, with the south (with its ‘latin’ influence? celebrating childhood less?) producing less ‘imaginative children’s writing’.

Entertaining books for children are obviously written in all countries, but to get back to my first question, do countries with an English heritage still produce the greatest proportion of imaginative writers for the young? Whilst nursery rhymes or similar verses are featured in most countries, what is it about the English that makes them the only race that claims that ‘Mother Goose’ is a work of art?

Long may we remain children at heart, treasure our heritage, our children, and let our imaginations fly free to create what we hope publishers will also recognise as works of art.

Acknowledgement : The source of some of this information has been Encyclopeadia Britannica 2001