I think my notes on the family history will probably just stay in the archive rather than be aimed at creating a book for publication. However, in writing for children, I may use some characters and incidents in stories. We’ll see.

Some ancestors were ‘normal’. My parents were ‘normal’, but the family-tree has a few twisted branches.

Mum and Dad, and my grandmother on my mother’s side who lived with us, all read to me when I was a child…and library books for their own pleasure in the evenings. My parents thrived on entertaining, which meant debate/discussion with friends and wider family, and when I reached adulthood, my own friends included playwrights, actors, wits and some of the most learned and well-read scholars in the land. I’m sure they were all influential in my writing voyage. But could my love of books also be in the genes?

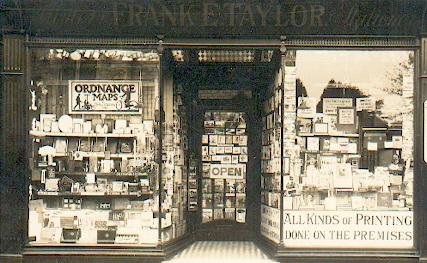

I never knew my great-grandfather Frank E. Taylor. He was an author, printer, stationer and bookseller in outer-London. His Dictionary of Lancashire Folk Speech was published in 1901, and he also wrote and self-published volumes of poems. He printed the works of his friends, too – one of which was Ernest Hartley Coleridge (whose name was the origin of Ernest as my middle name). He was the grandson of the famous poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. I have a copy of Ernest’s unpublished poems. He wrote an obituary to my great-grandfather, in which he stated that, at the back of the stationery shop, Frank had a ‘den’ where many of the poets and writers of the day would gather for discussions, and to be entertained.

Frank E. (Francis Edward) Taylor’s shop

He must have also been an avid and very regular theatre-goer, for I have much of his collection of hundreds of play-bills, with details of performers from the 1860’s provided as scribbled notes around the margins. He also collected engravings, particularly illustrations for books, and I have a small attache case full of those, too. But great-grandfather Frank was embarrassing.

He was ‘different’. He was the local eccentric, lunatic, nut-case… I’m sure he was called all those and a lot more. He was respected for his knowledge by his friends (who had often been initially summoned to his den, rather than invited), loved for his stories and dramatic rendition of poetry, and adored for his wit, but there were not many politicians or local dignitaries who did not despise him, for none were safe.

Every day or two, he would make up a satirical poem, a squib, making fun of some council decision he felt inappropriate, a local member of parliament, a new police regulation… These were printed on his press and, I believe put in his shop window and distributed freely to his customers. His shop was the site of much laughter from patrons, and indignation from those attacked in his verses. Independent Franky, as he called himself at election-time, was someone politicians hated, no-matter what party they belonged to, for in the most part, in verse, he proclaimed them self-centred or worse.

The trouble was, not every cause he fought for was a worthwhile one. He started to be considered someone ‘trying to hold back progress’. No sewage running down the road in pipes for Franky – it would spread diseases far and wide! He campaigned for the retention of cess-pits. In order to escape the controversies, my grandfather, Ernest Taylor, spent as much time as he could road-racing on the super-lightweight bicycle he had made.

In standing up for ‘people’s rights’, in one battle, Frank E. was required to appear before the local magistrate for refusing to put a street number on his door, gate, or anywhere else on his property. This was the last straw. My grandfather, who had, by now, left the family business and obtained a job in a grocery store in the town, decided to move a long way away.

After years in the stationery, food and retail trades, Ernest decided to abandon all that he knew to become a farmer – for which he had zero knowledge or experience. He was going to be a pioneer, and in 1912 he took a 100 year lease on 14 acres of land on the outskirts of Letchworth – a new town that mainly only existed on the plans.

Ernest invited two others to join him. One was Thomas Flaws, the son of the editor of the Bedfordshire Times newspaper, who also had ‘limited’ farming experience, to say the least. The other was Gertrude Matilda Beaumont, the daughter of the owner of the grocery store where he worked. Though Ernest asked her to marry him so they could set up this venture together, she declined. She would live unmarried with them both first, to see if she liked the lifestyle.

Was this ‘small-holding’ going to be viable? Was it a wise decision, in 1912, for an unmarried young lady to move in with two men in an isolated house on the edge of civilization? The scandal! What did her parents say? What did the neighbours in London say? What was their reputation in Letchworth? …And what a big change to leave a comfortable home with a maid to find that, at her new home, there was no flushing toilet, no bath, no hot water, no income, no mechanisation – just 14 acres of untamed land.

Gertrude eventually did marry Ernest. Ernest died when he was 95, and Gert at 99. During the whole of their married life they never had a day when they were not sharing their house with someone else …but I’ll have to write more about them and the way they worked the land at some other time.

As I sit here in my own ‘den’, with many of my great-grandfather’s books beside me and my writing buddies visiting me in person or by email, I definitely feel I am following in his writing footsteps, and that his spirit watching over me. I just wonder how crooked people will consider my twig on the family tree.

(At times when ‘writer’s block’ sets in, adding some more notes to the family history often makes the words start flowing easier in other projects.)