Picture books are written to provide young children with a roller-coaster ride of emotions. Similarly, we plot a journey for the older reader, leaving spaces in the text so they can use their imagination to see themselves beside the characters, but it’s by the way we tell the stories that we cause each reader to feel the characters’ pain, doubts and passion. In a second in music, a simple change in key, harmony, melody or rhythm can shift a listener’s joy to deep despair (or the reverse), but it’s not so easy for a writer. Perhaps it really is true that writers, who agonise over choosing perfect words, all wish they were musicians able to express themselves directly through their playing.

Calligrapher Ann Hechle has described how verbal orchestration in poetry also manipulates the depth of our feeling so that our mind, imagination and almost every part of us is engaged. The flow of Latinate words like ‘consider’ and ‘recognise’ contrasting with the thump in the guts Anglo-Saxon ‘gripe’, ‘groan’ and ‘grunt’; long and short vowels; tempo and stress; volume and density; onomatopoeia where sound shades into meaning–these are felt as physical sensations, stirring our brain’s deeper interpretation.

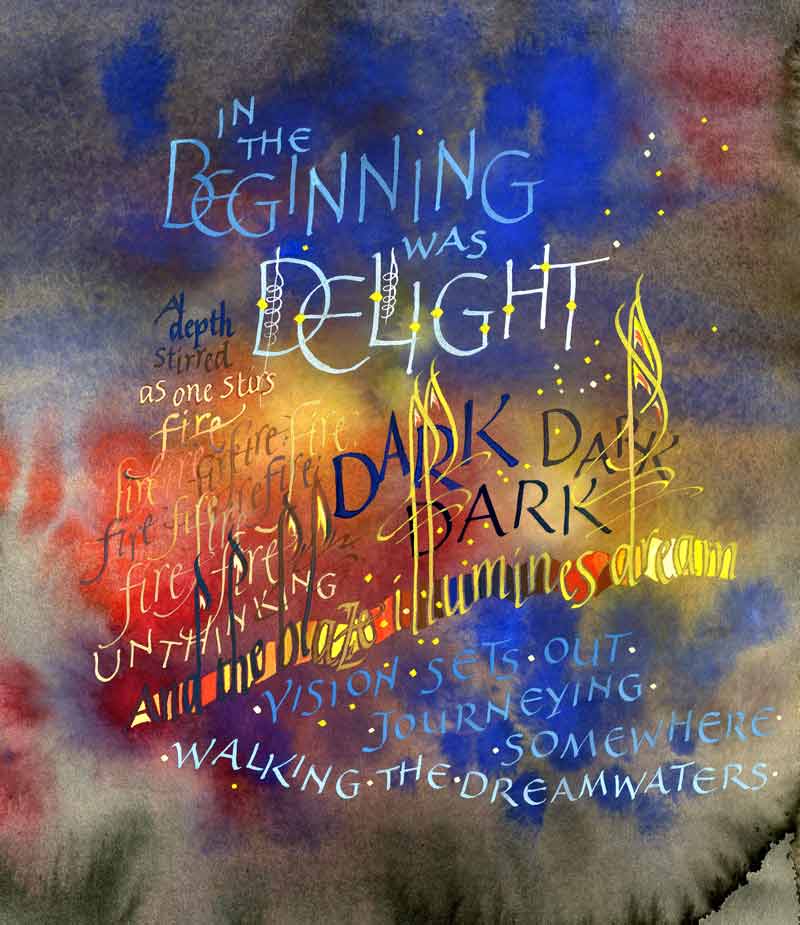

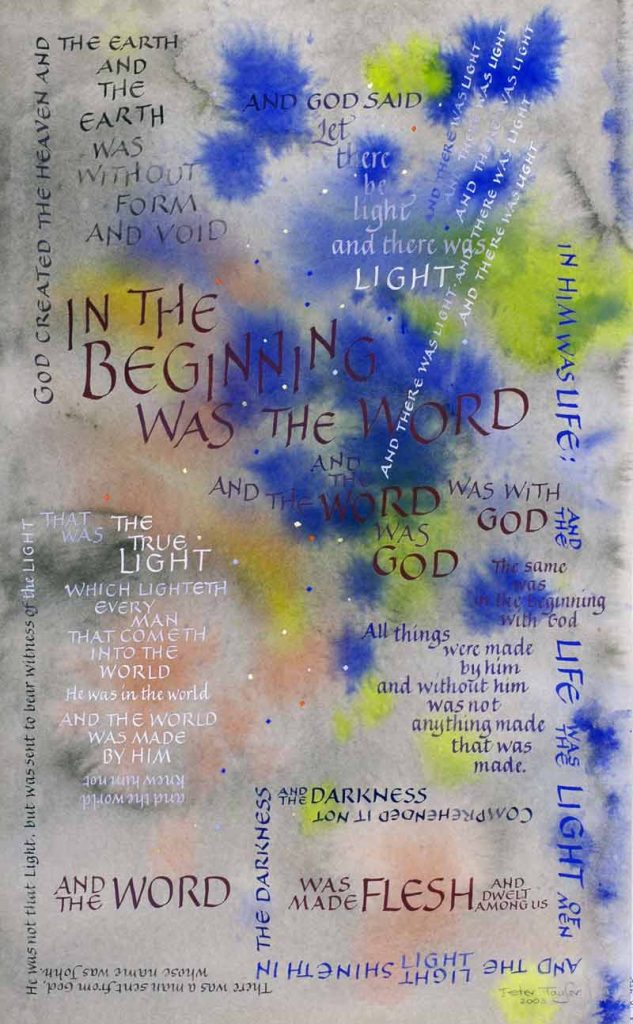

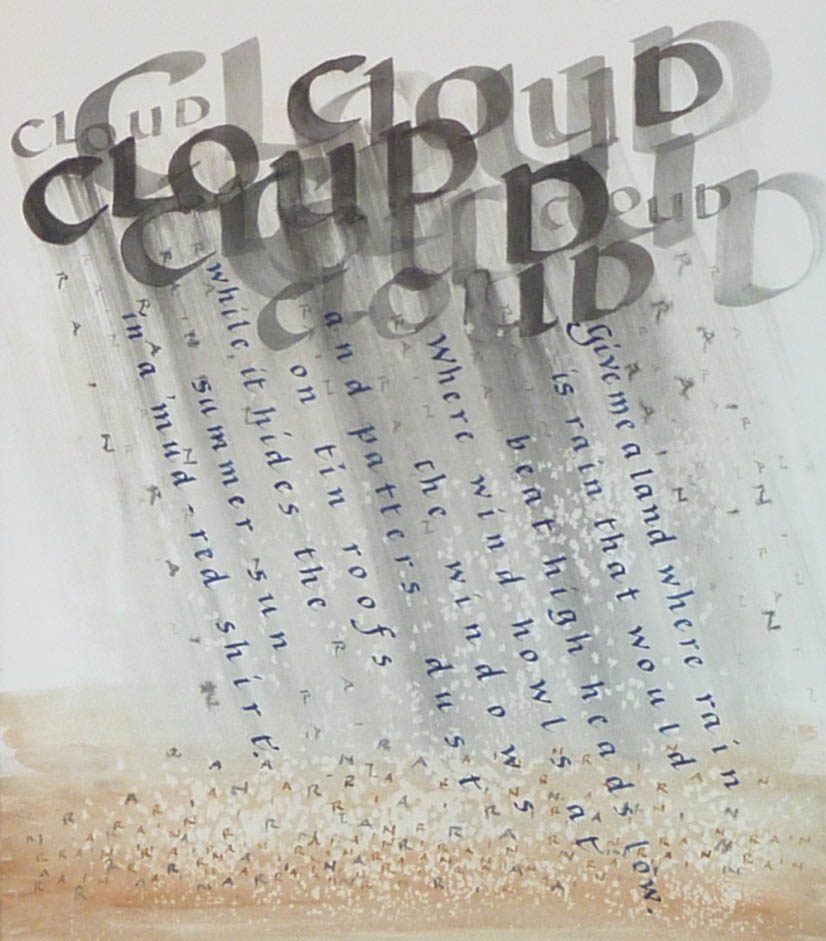

In such a world of feeling, it’s therefore surprising to me that children of all ages are not encouraged more often to interpret words visually, un-restrained by a standard size of letters and a requirement of regimented rows of words. Isn’t it natural to want to write about crashing waves by using letters and words that heave and tumble on …well …wave shaped lines, and in appropriate colours? And why not sometimes use larger and bolder letters for those words emphasised most in speech, as pioneered by Hechle in the 1960s? Such freedom may foster creative writing by children and adults alike, or engender an artistic response to any favourite text.

Text from Relearning the Alphabet by Denise Levertov

In the beginning was delight. A depth

stirred as one stirs fire unthinking.

Dark dark dark. And the blaze illumines dream.

Vision sets out

journeying somewhere,

walking the dreamwaters.

Designing the layout for words as an outward spiral may be appropriate for stories that unwind, such as: ‘Will you walk a little faster,’ said the whiting to a snail, ‘there’s a porpoise just behind us and he’s treading on my tail.’ Conversely, some stories wind up and can be written as an inward spiral, for example: ‘This is the cow with the crumpled horn that tossed the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that lay in the house that Jack built.’ And as you will see, based on a black and white artwork by Ann Hechle, I have used this spiral technique and others in my combination of biblical passages.

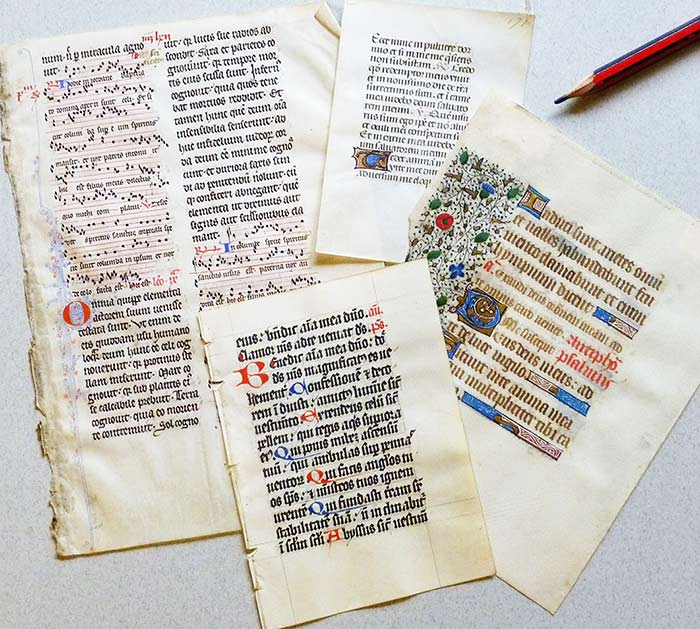

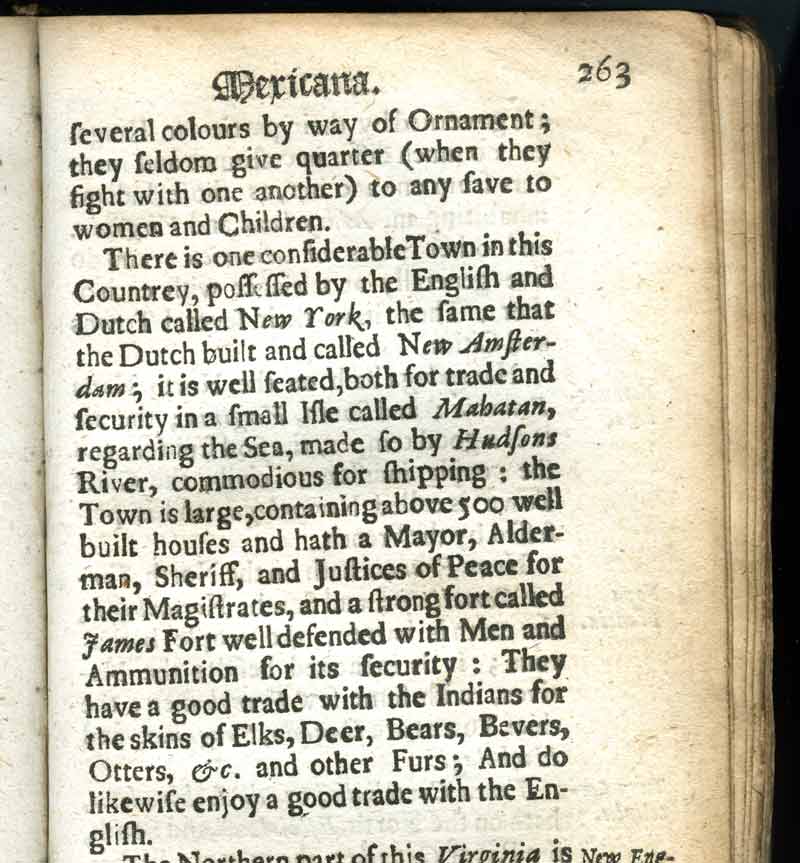

Not all children get hooked on reading and writing by initially listening to or reading stories. Some may arrive at the endpoint by predominantly first developing a love of words and of books as objects. When I stage a ‘Hands-on History of Books and Writing over 4000 Years’ experience in schools, even reluctant readers seem to enjoy handling a 2000 BC cuneiform clay sales docket, holding a hand-written vellum page from a 13th century medieval book without using white gloves, a page from one of the world’s first dictionaries printed in the 1480s, peeping inside Victorian picture books and deciphering a description of New York published in the 1679 that says that it has ‘…above 500 well-built houses’ amongst other treasures (and most then want to read more about early New York).

Some children may come to enjoy words and reading after calligraphic exploration. From playing with the word ‘rain’…

…research could next find a poem that is fitting for similar presentation, with reading undertaken in the process enjoyed more than expected:

This Land by Ian Mudie

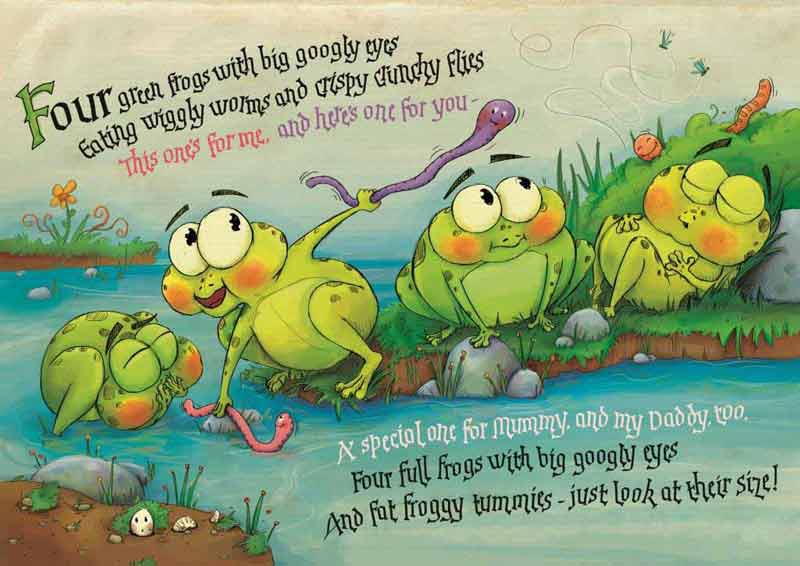

Designing calligraphic letter shapes can influence and add joy to creative writing, too. Letters with triangular serifs like webbed feet, for example, can give impetus to write about frogs, ducks or sea-gulls.

Verse and calligraphy by Peter Taylor Art by Anil Tortop

We can arouse young children’s interest in books with colour and quirkiness. But what sort of books are teens excited by? What kinds of bindings and book structures do they explore? I taught ‘Book Cover Design’ workshops to children aged 7 to 17 at the Queensland State Library. Participants used pens, scissors, paste and coloured and decorative papers to produce dust-jackets for Reference books of their choice (that were later re-shelved in their new covers). The children created the most eye-catching bold designs, but I wonder what they would have produced if they had been offered a wider range of materials and allowed more time, especially to read the books thoroughly. Would they have created a quilt cover for a book of poems titled On Going to Bed or placed hamburger recipes in a container shaped and covered to resemble a Big Mac?Would they have modelled or sculpted mountain ranges to sit on top of the pages of Lord of the Rings, as famed designer-bookbinder Philip Smith has done?

Or designed a ‘Book Stack’, as Mike Stilkey does?

Maybe the children would have produced something even more original.

How many books do teens smell? Are they encouraged to write, design and bind their own books?

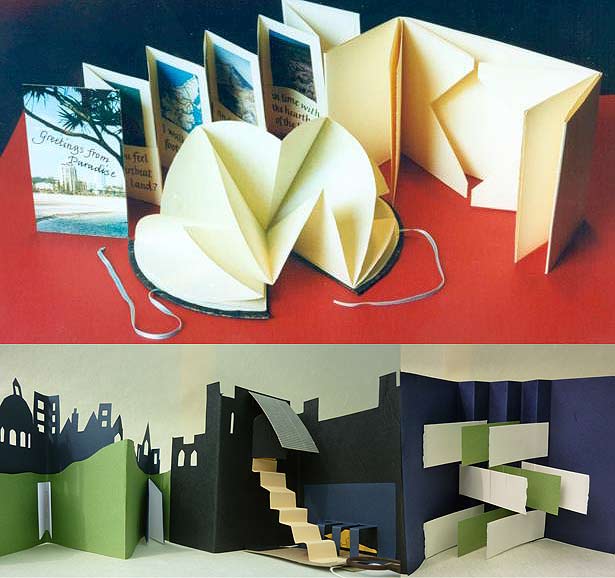

Is it possible that first creating a book with a special structure can provide the stimulus for writing a story to fit inside it? Or will a story provide ideas for a unique and satisfying way to display the text?

I hope children of all ages (and adults) are encouraged to explore the totality of the world of words, of language, writing, calligraphy, exciting layout designs and books of every form and structure until these become a rich, integral and important part of their lives. Sustenance for their creativity and creative thought. Let us give them experiences to savour and help them to respond with joy in their own way …to the extent that they want to bungee-jump into, read and devour our offerings of all genres with relish.